- Home

- Iván Monalisa Ojeda

Las Biuty Queens Page 8

Las Biuty Queens Read online

Page 8

On that last afternoon, Juanita’s was packed. We sat down at a table in the back. I ordered the grilled chicken breast with extra onion, yellow rice, and black beans. All Lorena ordered was a small chicken soup.

“That’s all you want? I told you, it’s on me!”

“Ay, no, thanks. I’m still sort of high. I was sewing a cape for Francesca. I had to get it done last night, so the loca had to give me a little you-know-what to keep me awake.”

“I’m sure I have no idea what you mean.”

As soon as I said it, we burst out laughing.

We capped off our feast with an order of flan. I devoured it. Lorena only had two spoonfuls. I paid the bill and we started to walk uptown. It was summer and night was falling. The streets were bustling. The nice weather here is so f leeting that New Yorkers always take as much advantage of it as they can. Music and voices could be heard until dawn.

Walking through Columbus Circle, we made eyes at a couple boys walking by.

“Ay, loca, did you see that boricua?” Lorena asked me.

“Yeah, Puerto Ricans are next-level gorgeous.”

“True that, and I remember I used to be in love with an Ecuadorian.”

“I never knew you were in love with a ñaño.”

“You better believe it, niña. How do you think I cooked you that professional-grade ceviche the other day at Melanie’s?”

“Uy, sí. That’s right. With the tomato sauce and everything, can you imagine.”

“Well that’s what I made for my husband every weekend. When I didn’t have to go work in the factory, obviously.”

“What factory?”

“I did sewing for some Koreans. There must have been thirty of us sitting at our sewing machines. Sometimes we’d work twelve hours with no break. Technically our shifts were eight hours, but the Koreans always asked if we could stay late. If anyone said no, they’d usually get fired a few days later.”

“I’m surprised you didn’t start hustling like all the other girls.”

“Ay, no. One time, Vivian, this girl whose shows I used to make dresses for, invited me out to the bar at Sally’s. That place on the first f loor of the Carter Hotel, acordái? Back then I was already living as a woman 24-7. And I was on a full dose of hormones, so I looked gorgeous, gorgeous. I’d left Hugo back in Chile, so from then on I was always Lorena. Mind you, I always sewed the name Hugo Loren Design into all the clothes I made. To represent all that I am.”

The fresh breeze, which swept through the streets looking for bodies to envelop, chose ours. Sirens from a passing fire truck brought us back to New York’s asphalt reality.

“Like I was saying,” continued Lorena, “Vivian, who in addition to doing shows was also picking up tricks at bars, introduced me to a guy and told me to take him upstairs. She said he was staying in the hotel and he’d give me a hundred bucks. I hadn’t even managed to say yes or no when bam! I was with the guy in the elevator going up to his room.”

“And?” I asked her, with a trace of morbid curiosity.

“Ay, no, the guy wasn’t even handsome. It was a tough pill to swallow, if you know what I mean. Fat, pale, one of those guys who smells like puke. You know, a human vomit. You can imagine what happened next. On top of it, AIDS wasn’t an issue yet, so no one was using condoms. That experience was my debut and my finale as a prostitute.”

“Let’s go over and sit in Central Park, and you can give me a little dose of life and love,” I proposed as we passed the statue of Christopher Columbus.

“A little dose of mortality, you mean.”

“I guess it’s all the same.”

We went into Central Park and sat down on a concrete bench under some hundred-year-old trees. I thought of how we must have looked from afar, like part of some great work of art.

“You’re the lookout,” she told me.

“Okay,” I said, standing up and switching into radar mode.

She did a bump and handed me the bag. Then I sat down and she stood up to be the lookout. I did a bump. We sat down side by side.

“That’s what I’m talking about, weona,” she said, looking at me, and we both started to laugh. “How many years has it been since you were in Chile?”

“Almost ten.”

“Girl, that’s nothing. I’ve been away more than thirty.”

We were silent for a moment.

“Do you miss it, Mona?”

“Sometimes I do, sometimes I don’t. You?”

“Yeah, sometimes. My mom turned ninety a few months back. I sent my sister two hundred bucks to throw her a little party. I sent her a dress, too. It was pink, her favorite color.”

“Did they send you pictures?”

“I don’t like seeing photos. I’d rather imagine what they all look like now. It’s been so long, I don’t know if I’d even recognize them.”

When I think back and remember the energy of that moment, I know we were both thinking the same thing. Night had fallen, people were headed out of the park, and the new fauna were coming in.

“Look, I think those two are cruising,” Lorena said.

“Definitely. I was into cruising back in Chile. I’d go to the parks, up to Santa Lucía hill and the Lira underpass. Not anymore, though. I like peep shows better. Less walking around. It’s faster and more direct.”

“I’m all about the gays-for-pay at Port Authority.”

“Oye, I feel like we’re getting stuck here. Let’s keep moving,” I said, standing.

We left the park and walked a few blocks uptown along Central Park West so we could turn toward Columbus Avenue. Lorena wanted to see if she could find anything interesting over there. She often went around the streets of Manhattan looking for stuff people had thrown away. She found all kinds of things, from Broadway costumes to Chanel handkerchiefs to Lancôme makeup. Even a black-and-white checkered jacket with a Bloomingdale’s label that she gave me one Christmas. I still have it, to this day.

We walked slowly to 46th and 9th, where I was renting a room. Back then I lived with Francesca, Melanie, La Fernando, and La Vivian, each one of us in her own room. Lorena was our habitual guest. She’d stay one night in one of our rooms and the next night in another.

When I moved to Washington Heights, our visits were few and far between. I heard Lorena moved to a hotel on 52nd Street between 9th and 10th. I heard that once, in the middle of Manhattan winter, on one of those nights when the streets were full of snow, she decided to go out to the grocery store in the middle of the night. They told me that, either on her way to the store or on her way back, her heart said basta and she collapsed. She had an ID on her, so it was easy to identify the body and get her information. It turned out she had family in Canada who dealt with the body.

I like to think that they cremated her and sent her ashes to Villa Alemana. That they left Lorena under the tree where little Hugo would kneel to pray as a boy. Never again did I see Doña Rosa or eat another one of her beef empanadas.

A Coffee Cup Reading

I WAKE UP DESPERATE. I know what I’m doing. I’ve been lighting candles for years. Floating folded-up scraps of paper with his name and my name in cups of water sweetened with honey. I’m in love. As soon as I wake up, I dial the number.

“Hi, Niña. It’s me. I need you to do a coffee cup reading. I can give you five bucks today and the other five on Friday.” Before I hang up, I add, “And could you make me a little cup of coffee, por favor? You’re a doll.”

I get up. I go to the bathroom. All I do is brush my teeth and wash my face with cold water. I get dressed quickly. I pull twenty dollars out of my wallet. I walk toward Niña’s, which is less than two blocks away. I stop by the bakery. It’s eleven in the morning. It’s still early, I think, as I go in to buy the last of their fresh bread. I pick up my phone again.

“Oye, Niña. What kind of bread do you want? Just in case you feel like making me some fried eggs, too.”

I ask the Dominican girl behind the display case for two loaves

of pan de manteca and one loaf of pan de agua.

When I arrive at the building, I don’t even bother to see if the elevator’s working. I climb the five f lights in a matter of seconds. The door to the apartment is already open.

“Niña!” I call out once I’m inside.

“What’s up?” a voice answers from the kitchen.

I zoom down the hall and stop right in front of Niña. She’s sitting next to the window that looks out onto St. Nicholas Avenue. She looks at me with her big, dark eyes. She holds out her hand.

“Give me the five dollars.”

Once I sit down, I take the bills out of my pocket and give them to her. La Niña snatches them from my hand and stands up from her chair.

“Be right back,” she says.

“Wait, I brought bread for us to have with the eggs.”

“Calm down. You’re super anxious. Take some water out of the fridge. It’s chilled. I’m leaving the door open. Don’t lock it. I’ll be back soon.”

She exits quickly. Running, I might even say. I stay seated. I breathe deeply. I stand up to look for a cup. I find a large, clear one made of glass. I fill it with water that I take out of a gallon jug in the fridge. I drink slowly. It’s ice-cold. It refreshes me. It relaxes me. I sit down again. I feel a sense of calm surrounding me. There’s seriously something special about the water at Niña’s house. From where I’m sitting, I look at the window that opens to the street. I see the church across the way. It’s a concrete church, unpainted. Niña lives on the fifth f loor, so all I can see is the cross. Far off, I can hear the sound of traffic. The f lapping and cooing of a few pigeons who come to rest in the window snaps me out of my daze. I sense the apartment door open.

“I’m back,” says Niña, walking toward the kitchen. “Have you simmered down?”

“Ay, sí. There’s something special about this water of yours.”

“That’s the truth,” she says as she smokes.

“I brought some pan de agua and pan de manteca.”

“Okay, pass me the eggs from the fridge. They’re going to be delicious.”

“Your eggs always turn out delicious,” I say, opening the fridge and passing her the eggs from the upper compartment. “I’m going to have some more water.”

“Of course, bebe. It’s good for you. I’ll do your reading after you eat.”

For a moment there, I’d forgotten why I came. My anxiety returns.

“Sí, Niña, I need a reading. He hasn’t called me in a week. Do you think he’s seeing some other loca? He always calls me on Thursday, but yesterday? Nada.”

I’m still talking when Niña puts a plate down in front of me.

“Eat.”

I start to eat obediently.

“Mmm,” I exclaim. “This is amazing, especially with the onion and tomato you put in.”

My anxiety makes me forget I’ve also brought pan de agua. I stand up, and before I finish the eggs, I grab a big piece of bread and load it with everything left on my plate.

“Ay, Dios mío. I love watching you eat,” La Niña says, laughing. “You eat with so much gusto.”

“You’re just such a great cook,” I tell her, my mouth still full.

“Now I’ll make the coffee.”

She takes a percolator coffeepot from the stove and washes it carefully in the sink. The pigeons who f lew away come back to rest in the windowsill, f lapping their feathers and cooing.

“Look. Pigeons never came here before. What happened?”

“No idea,” says Niña, indifferent. “Okay, the coffee will be ready in a second.”

In the meantime, she takes out a shiny white cup and puts two spoonfuls of sugar inside. The coffee is ready. She serves me even less than half a cup. Then she puts some in her cup. She sits down, as always, next to the window. She lights another cigarette.

“Save some coffee, so we can do your reading.”

“This coffee is perfection,” I say nervously as I drink it.

Niña picks up the phone and dials a number.

“What were the results?” she asks someone. “Okay.”

She hangs up. I see the expression of disappointment she shakes off with a sigh.

“I know,” I tell her. “Your numbers didn’t win.”

“Well, no. But it’s okay, maybe next time.”

“Ay, Niña, if you just saved all the money you spend on lottery tickets, you’d be rich. What you have is a bad habit.”

“Everyone has their vices,” she says, looking me in the eye.

“That’s true,” I tell her, lowering my head and remembering people in glass houses shouldn’t throw stones.

We sit for a few seconds in a silence that’s interrupted only by the pigeons’ f lapping and cooing.

“Okay, let’s do this. Come closer, time to start.”

I sit down in the chair facing her. She pours what’s left of the coffee into my cup and says to me, with gravity, “Remember not to drink it all. You should drink three sips and leave some coffee. The first is for you. The second is for your home. The third is for the knowledge you seek.”

Once I’ve taken the three sips and have a bit of coffee left in the cup, La Niña puts it on the stove over low heat to dry out what’s left of the coffee. A moment later, she picks up the cup, puts on her glasses, and starts to look.

“What do you see, Niña? Tell me what you see,” I ask her anxiously.

“I see money entering your house.”

“Ay, please. You always say that. Tell me about him. Is he with someone else? Why hasn’t he called?”

“Patience. And don’t talk to me like that. The spirits will get mad and I won’t be able to read anything.”

“Okay, I’ll calm down,” I say with deference.

“Yes. Look.” She shows me the inside of the cup. “See that big stain? That’s him. And he’s facing you. That means he’s thinking about you.”

“Really? So he’s going to call me?”

“Yes, take a look. See those grounds in the shape of a person? It’s a person of great stature. He’s tall, isn’t he?”

“So tall. He’s six foot three,” I reply, trying to make out the person who’s supposedly inside this coffee dust. “So, he’s going to call me?”

“Yes. Relax.” She sits there looking pensive. “Either today or tomorrow he’ll call.”

I let out a sigh of relief. It feels as though a weight’s been lifted.

“More coffee?” asks Niña.

“No, I want some more water. The coffee’s winding me up.”

I take more water from the fridge and sit back down. As I drink, I hear the pigeons again.

“Look, Niña, turn around. The window’s full of white pigeons.”

She turns around. She looks at them and says, “Poor guys. At least they’re free. You know they use doves for witchcraft.”

“Really? I had no idea,” I tell her, surprised. I’ve lived in New York for many years, but some things still amaze me.

“When I was a little girl and we lived in Bonao, in the Dominican Republic, we had a neighbor who did witchcraft. One day I was out on the back patio and I saw he’d left a cage of doves open. A few of them were hanging around the patio. Some had even come over to our side.” She pauses. “I thought about how they were going to be sacrificed. They were beautiful, so well groomed, well fed. They were nice and plump. Can I have some water?”

I stand up. I open the fridge. I take out the gallon of water and fill up a glass. I do all this as though it were some kind of ceremony. Niña takes a big sip.

“Like I said, the doves looked really plump. You can’t imagine how bad I felt for them.”

“Obviously,” I say, getting ahead of myself. “You saved them from being sacrificed and they all f lew to freedom. You have such a good heart, Niña.”

“No way. They clip doves’ wings when they trap them so they can’t f ly.”

“So what did you do?”

“What do you think? I grabbed a

few and cooked up a nice dove stew,” she says, opening her big, dark eyes wide.

“What?”

“Yep, I thought if the doves were going to be sacrificed, they might as well be sustenance for human beings. So I trapped them and made some dove soup that turned out delicious.”

I sit there with my mouth agape. Silently, I stand up. I need a fresh glass of water. I fill it up. I drink it all in one gulp. Then I sit down and start to laugh.

“Ay, Niña. Honestly, you’re too much.”

“Wait, that’s not the whole story.”

“Ay, no. There’s more?”

“Claro.”

“Well come on, spit it out. What happened? Did the neighbor figure out it was you?”

“Bueno, if you want me to tell you the rest of the story you have to go down to Habibi’s and buy me a few cigarettes.”

“Ay, Niña, don’t be like that, I don’t have much money left.”

“Today’s Friday. You’ll make money at the bar. And that man is going to call you. Listen to your little witch.”

I don’t know if it’s her prophecies or my curiosity, or a mixture of both, but I stand up and go down to the Arab guy’s store to buy two cigarettes. Just as I’m about to give him a dollar for them, my phone rings. It’s Niña.

“Actually, make it four. Trust me, the story’s that good.”

I buy the four cigarettes. And I run up to the fifth f loor to hear the end of the story.

I find Niña looking pensive, gazing out at the church with her back turned to me. The cross is her across-the-street neighbor.

“I love the view from your window,” I say, handing her the cigarettes. As I start to sit down, I add, “That Gothic style sometimes makes me feel like I’m in the Middle Ages.”

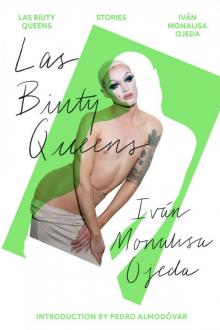

Las Biuty Queens

Las Biuty Queens